Travel photography is so exciting and satisfying in part because it requires us to capture every kind of image in all kinds of shooting environments. You could be heading out to shoot landscapes when suddenly a rare sighting of an animal transforms your activity into a wildlife shoot. Or you may be on the road for your next destination when you stumble upon a colorful local festival, and now you’re shooting portraits of the revelers. This rich diversity of subjects also creates one of the biggest challenges for travel photographers: how to be prepared for anything that comes our way. For beginning photographers there is some comfort in using the Auto mode that nearly every camera offers. After all, we’re more likely to get an acceptable shot this way, when the subject turns quickly from fast action to landscapes to the low light of evening, or to an indoor performance. But in most cases, your camera’s Auto mode, which attempts to make its best guesses as to what settings to use given existing conditions, will yield only acceptable photos and not the striking and memorable images we’re after.

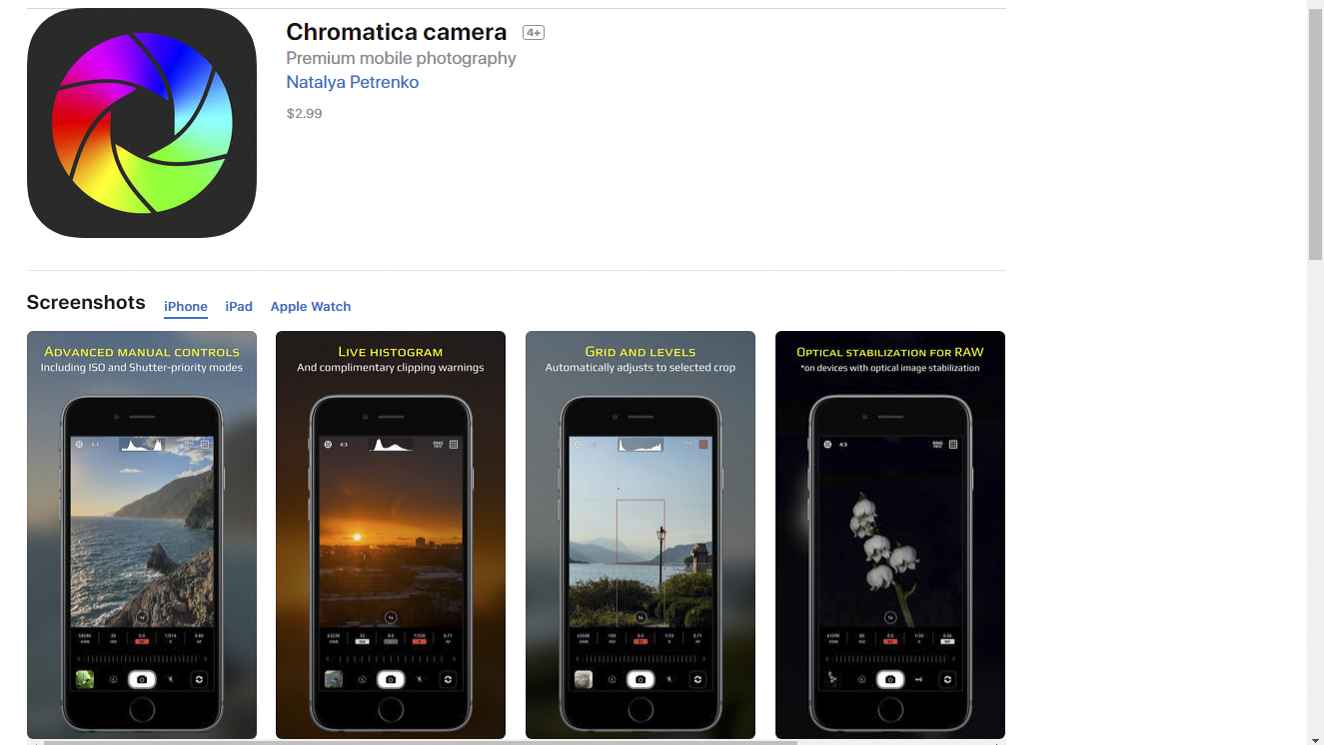

There is a better way. Take control of your images by learning how to manually set your exposure, focus, and other aspects of your photo. All advanced point-and-shoot cameras and all mirrorless and DSLR cameras allow you to set most functions manually. Even some basic point-and-shoot models have a way to go manual, but often this will involve options buried deep in a menu somewhere. And there are apps available for both iOS and Android smart phones that allow you to take manual control over your phone’s camera. I use an iPhone 6S, and I’ve found the “ProCam 4” app to work very nicely for providing control over the phone’s camera setting for exposure, focus, and flash. You can find it for less than $5 on the Apple App Store: ProCam 4 App. Even without using an app, most smart phone cameras do allow you to override the automatic settings by clicking on the part of the image you want to be in focus and used for the exposure setting; usually you can also set the exposure based on a different area of the image from the area that you want to be in focus. But the dedicated apps will give you greater control, as they allow you to choose the shutter speed, aperture (when not fixed), and ISO for each shot.

For this image of a whirling dervish in Goreme, Turkey, I wanted to blur the dancer so as to give a sense of the continual turning motion in the ceremony, so I used my camera’s shutter-priority exposure mode and selected a slower shutter speed. Buy this photo

The key to successfully using your camera’s manual settings is to learn how they work and to practice at home, long before you actually take a trip. Like anything else, selecting the settings we want on a camera takes practice. In this digital era, it’s easier to learn because you can see the results of each setting immediately on your camera’s screen. So dig out that camera user guide, or find it online, or search for a good tutorial. But do learn how to adjust the key settings manually.

The first manual setting every photographer should learn is how to turn off your camera’s flash. This sounds very basic, but I’m always amazed to see so many flashes going off in inappropriate places: museums that don’t allow flash photography, cultural performances, sports stadiums where the subject is thousands of feet away from the camera (the flash will only provide acceptable lighting for a few dozen feet, at most), and even the shy octopus exhibit at our local aquarium. Believe me, you do not want to flash the octopus. So learn how to turn your flash off, and be sure you actually do turn it off when you’re in a venue where flash is inappropriate or won’t help your image be better exposed. Remember that glass reflects light, so you don’t want your flash on when shooting through windows of a vehicle or the glass windows of animal enclosures at zoos or aquariums.

Next, learn how to set your camera’s exposure manually. The light meters built into today’s cameras are very smart, but they are also easily fooled by tricky lighting conditions. The most common problem is backlighting. If your subject is lit from behind, as many outdoor subjects are, your camera’s auto mode will likely expose for the brighter background and will leave your main subject underexposed. You can adjust for this is several ways. It may be good enough to just use your camera’s exposure compensation button to dial in, say, one extra stop of exposure. Use your camera’s LCD screen and (if it has one) the histogram, to see how the subject is exposed with varying levels of compensation. In some cases (if your main subject is quite close to the camera), you can use fill flash to fix backlighting problems. To do so, manually turn on your camera’s flash, or attach a separate flash unit, and choose the setting for “fill flash” or “balanced TTL” (through the lens) flash mode. Again, check exposure using your camera’s screen and histogram. I find I usually get good results in tricky lighting conditions by using my camera’s spot metering mode, which tells the camera’s meter to use only the very center (or whatever area I select) of the image when choosing the exposure.

Other than allowing you to properly expose your main subject, manually setting the exposure also gives you control over what combination of shutter speed (how long the exposure lasts), aperture (how wide the lens is open), and ISO (how sensitive the camera is to light) you want for each shot. If you’re shooting fast moving action like sports or wildlife, you will likely want to choose a fast shutter speed to freeze the motion (unless you want a blur effect as an artistic choice). If you’re photographing a waterfall or sky and want to get some nice blurring of the water and/or clouds, you will probably want to choose a slower shutter speed. Many times you want only certain parts of the image to be in focus. A wide aperture (low F-stop number such as f/1.8) will give you a shallow depth-of-field, allowing only one part of the image to be in focus and blurring the other parts. Conversely, a narrow aperture (high F-stop number such as f/16) will allow all parts of the photo to be in focus. The final element determining exposure is the sensitivity of the camera’s sensor, measured by an ISO number. Select a higher ISO (such as 1600 or above) only when you really need the extra sensitivity for very low-light subjects when a longer shutter speed or wider aperture is not suitable. When you use very high ISO settings, the image will tend to have a lot of noise. Today’s cameras are getting better at limiting noise at high ISO settings, and there are ways to reduce some of the effects of the noise using post-processing software, so my approach is to use as high an ISO as is required after considering the range of available shutter speeds and apertures.

To capture these professional beach volleyball players in sharp focus and to freeze the moment, I selected single-focus-point focus mode and chose the exact spot in the viewfinder where the players would be positioned, and also used my camera’s shutter-priority exposure mode to select a very fast shutter speed. Buy this photo

The other major type of manual setting that you need to know how to use is focus. Most cameras today do a pretty good job of choosing the right part of the image to focus on, but they often need some help from the photographer. From simple smart phone cameras through professional DSLRs, the autofocus function almost always lets the photographer select what part of the image they want to be in focus. If you keep your camera in fully autofocus mode and don’t help by selecting where your main subject is, it may very well guess incorrectly and put another part of the image as the center of focus. So, learn how to select the focus point even while letting your camera’s autofocus mechanism actually choose the focus distance. Sometimes a camera’s autofocus capability may not work for the conditions under which you’re shooting, and in these cases you need to turn off autofocus completely, and focus in manual mode. Some instances when this is necessary are when shooting in very low light conditions, or when shooting in poor contrast environments (for example, your subject’s texture looks a lot like that of its background, or you’re shooting into the bright sun). In these cases, turn off the autofocus function and adjust focus manually until the subject looks sharp.

It’s still fine to walk around during your travels with your camera set in fully Auto mode, just in case something very unexpected comes up. But do know how to set the main functions manually so you’ll get the best possible images in the 95% of the shooting situations when you do have time to set up first.

Want to read other posts about photographic techniques? Find them all here: http://www.to-travel-hopefully.com/category/techniques/

Do you have tips and tricks you can share on manually adjusting the camera’s settings to get great shots? How about a time you kept the camera on Auto mode and got disappointing results? Please share your thoughts using the comment box at the end of this post.